The Fairshare Model: Chapter Seven

Karl M. Sjogren

2015-04-10

By Karl M. Sjogren *

Section II: Context for the Fairshare Model

Chapter 7: Macro-Economic Context-Economic Growth

Preview

- Foreword

- What About Job Growth?

- What policies hold promise to economic growth?

- Four Prescriptions for Economic Growth

- Another Prescription for Better Capitalism-Restore Dynamism

- Onward

Foreword

The Fairshare Model is a tool to address a micro-economic challenge—how to allow average investors to participate in providing the venture capital that entrepreneurial companies need on terms that approach what professional investors get. It has implications for the macro-economic challenge of spurring economic growth. This chapter considers the macro-economic climate by calling attention to analysis by some distinguished economists on to how to respond to economic crisis.

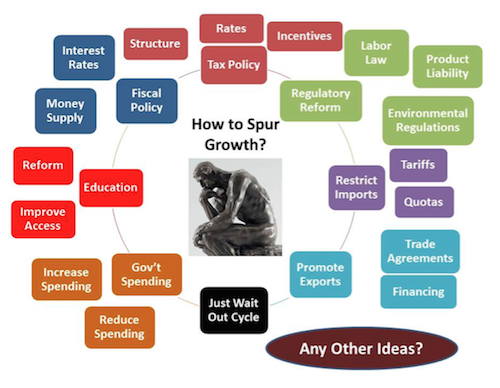

What policies hold promise to economic growth?

A major challenge facing America, indeed nearly all countries, is how to generate economic growth. Rodin's The Thinker illustrates the basic options available to policymakers.

With the exception of import restrictions, each policy avenue has been pursued to some degree since the Great Recession. None have been remarkably effective; this downturn exposed structural issues for which there are no obvious solutions in the playbook of economists. Advocates of any given approach to argue that the right policies haven't been adopted with sufficient vigor. In response, opponents argue that the lack of success is evidence that it's not the right approach at all. Political gridlock about what to do has made "just wait out the cycle"the default response.

So it goes.

How did we get here and what policy initiatives hold the most promise? The following explanation is from Robert E. Litan's and Carl J. Schramm's 2012 book, Better Capitalism (bold added for emphasis). [68]

The 1950s and 1960s were the halcyon days of "managerial capitalism,"when large firms such as General Motors, Ford Motor Company, U.S. Steel, IBM, and AT&T (in its previous monopoly incarnation), among others, were the driving forces of the U.S. economy. Taking advantage of the pent-up demand for consumer goods during World War II, large firms expanded their reach into new markets at home and abroad. They used their economies of scale, access to internal capital, and in-house research labs to generate new products, drawing on technologies that had been developed during or before World War II. This managerial capitalism delivered rapid growth and thus rising living standards for almost three decades after the end of the war. Indeed, our particular brand of this capitalism was not only envied, but feared. In the late 1960s, European intellectual Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber warned European governments and citizens that without aggressive counter-measures, the multinational companies birthed and headquartered in America—the quintessential managerial capitalists—would dominate the world economy.

But then the U.S. economy hit the proverbial wall in the early 1970s. Inflation had been edging up throughout the Vietnam War, eventually leading to a run on the dollar that forced the United States to quit exchanging gold at the price fixed after World War II. Soon thereafter, the fixed exchange rate system that had governed world currency markets and international trade that had been in place since World War II came undone. The coup de grace was the quadrupling of oil prices in 1973, which pushed both inflation and the unemployment rate nearly into double digits—then post—Depression highs. Even though growth later resumed and the unemployment rate fell back to near 6 percent, inflation stayed uncomfortably high until the economy was hit by yet another oil shock, this one in 1979 during the Iranian hostage affair. From 1973 to 1980, stock prices dropped in real terms (adjusted for inflation) by roughly 40 percent, reflecting a loss of faith in the managerial capitalism that at least until the first oil shock had produced such rapid growth and widely shared prosperity.

There was ample reason for the loss of faith. Big Auto and Big Steel—along with steadily Bigger Government—that helped define managerial capitalism proved too bureaucratic and uninventive to withstand the seeming onslaught of cheaper (and often better) imports from Japan and elsewhere. While many Americans feared the United States was thus losing out to the Japanese on the economic front, they had also been steadily losing faith in government. The U.S. military not only suffered its first-ever defeat in Vietnam, but the Watergate scandal that ultimately forced President Nixon to resign shocked Americans of both political parties. The decade ended with the seizure of the American Embassy in Iran and the humiliation of U.S. government employees being held hostage for over a year, unable to be rescued by the one failed military attempt to do so.

In one narrative, what saved America and rejuvenated its economy was the election of the optimistic, anticommunist, free market enthusiast Ronald Reagan to the presidency in 1980.

Rather than wade into contentious political waters about the correctness of this explanation, we suggest here that an uncontroversial but important contributing reason for at least the economic turnaround was the transformation of the U.S. economy from managerial to entrepreneurial capitalism. This apparently new form of capitalism was not new at all, but is in fact what powered the American economy from Revolutionary times until the early 1900s: the cleverness and hard work of waves of entrepreneurs of all types whose efforts gradually lifted the living standards of American citizens.

Entrepreneurs began to take center stage in the U.S. economy again in the 1970s (before Reagan was elected) with the formation of such companies as Intel, Microsoft, Apple, Federal Express, and Southwest Airlines, among others. But entrepreneurial capitalism really took off in the 1980s and 1990s and flowered under presidents of both major parties. [69]

Also from Better Capitalism :

We argue that the "better capitalism"the United States needs now more than ever is one that fosters continuous entrepreneurial revolution —the economic equivalent of what Thomas Jefferson called for when he famously uttered, "Every generation needs a new [political] revolution."

Whether or not that statement is appropriate for governing, it could not be more relevant today as an economic proposition. For countries at the technological frontier like the United States, sustained rapid growth is only possible through the continued commercialization of new, disruptive—and, yes, revolutionary-technologies, products, and services. We are not sufficiently clairvoyant to predict what those technologies will be. Futurists in the past have missed the mark, and no doubt their heirs today will be equally unsuccessful. [70]

What About Job Growth?

In the late 1990's, I saw a presentation by the head of the U.S. Small Business Administration that said that since the late 1970s, young companies had been responsible for more net job growth than all Fortune 500 companies! My first reaction as "I would not not have thought to compare the two."My second was "amazing!"

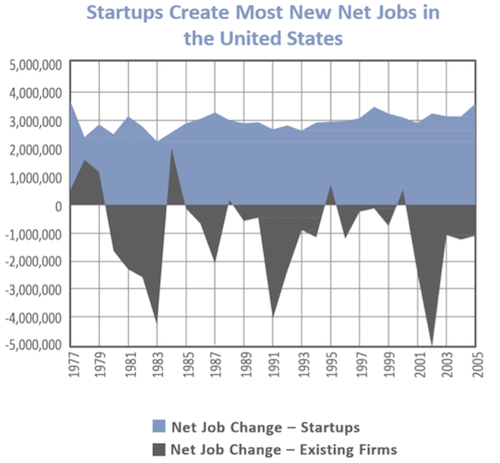

More recently, in June 2010, Dr. Tim Kane, senior fellow in Research and Policy at the Kauffman Foundation, authored a report, The Importance of Startups in Job Creation and Job Destruction, that made the following statement (bold added for emphasis).

Without startups, there would be no net job growth in the U.S. economy. This fact is true on average, but also is true for all but seven years for which the United States has data going back to 1977. [71]

The report includes the chart below, which shows startups adding about 3 million jobs each year from 1977 to 2005 and existing firms generally shedding jobs.

There is no obvious solution to the persistent job losses at existing firms. However, it is abundantly clear that start-ups have consistently been a source of good news on this front. One important way to encourage job creation, therefore, is to improve access of small companies to capital.

Four Prescriptions for Economic Growth—Better Capitalism

The Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation it is one of the largest foundations in the world devoted to entrepreneurship. Its website, www.kauffman.org has a set of engaging video sketchbooks. If you go there and search for "Better Capitalism", you'll see an animated explanation of Litan's and Schramm's four strategic policy initiatives to spur entrepreneurship and reinvigorate long-term economic growth. [72] They are:

1. Encourage immigration by high-skilled foreigners

2. Improve access to capital for new firms

3. Speed up commercialization of innovations at universities

4. Regulatory reform

This book, of course, is all about a way to contribute to their second initiative-improve access to capital for new firms, albeit on terms that are better for public investors.

Let's briefly discuss the other three.

Traditionally, the U.S. and other countries have benefited greatly from encouraging immigration by high-skilled foreigners and there is little reason to think that should not continue to be the case. Litan and Schramm write the following in their book.

Readers will surely recognize the names of these outstanding immigrants and the companies they founded and helped launch, but we'll bet not many realize that these individuals were all born in other countries: Alexander Graham Bell (AT&T), Levi Strauss (Levi Strauss & Co.), Andrew Carnegie (U.S. Steel), Herbert Dow (Dow Chemical Company), E.I. du Pont (DuPont), Charles Pfizer (Pfizer), David Buick (Buick Motors, later purchased by General Motors), Adolph Coors (Coors Beer), Henry Heinz (H.J. Heinz Company), James Kraft (Kraft Foods), William Proctor and James Gamble (Proctor & Gamble), Eberhard Anheuser and Adolphus Busch (Anheuser-Busch), Samuel Goldwyn and Louis Meyer (MGM), Marcus Goldman (cofounder of Goldman Sachs), and even Ettore Boiardi (Chef Boyardi). Add Sergey Brin (Google), Andrew Grove (Intel), Jerry Yang (Yahoo!), and Pierre Omidyar (eBay). [73]

President Barack Obama made a similar point when advocating for congressional action on immigration reform.

In recent years, one in four of America's new small business owners were immigrants. One in four high-tech startups in America were founded by immigrants. Forty percent of Fortune 500 companies were started by a first- or second-generation American. Think about that — almost half of the Fortune 500 companies when they were started were started by first- or second-generation immigrants. So immigration isn't just part of our national character. It is a driving force in our economy that creates jobs and prosperity for all of our citizen. [74]

The Fairshare Model complements implementation of Litan's and Schramm's third recommendation—speed up commercialization of innovations at universities—because it could improve access to capital by start-ups that license technology. A university might accept some payment in Investor Stock and/or a position in a licensee's Performance Stock.

The fourth recommendation, regulatory reform, is beyond the scope of this book. I will say, however, that companies in a financial turnaround situation must rethink strategy and processes. The same is true for nations in an economic turnaround. Starting in 1991, Japan's theretofore highly successful economy entered recession. Its failure to address regulatory reform are a major reason why many problems persist, nearly a quarter century later.

Better Capitalism, was published in 2012 as the sequel to a book that Litan and Schramm issued with William J. Baumol in 2007, Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism, and the Economics of Growth and Prosperity . Better Capitalism was written because the world changed dramatically shortly after Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism came out and the authors felt "we need an even stronger dose of entrepreneurial capitalism"than first proposed.

Here is an excerpt of a review of Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism that was in the July 7, 2007 edition of The Economist, a few months before the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the investment bank that heralded the financial crisis (bold added for emphasis) .

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 may have proved once and for all that capitalism is better than communism, but it did nothing to settle the debate about which model of capitalism is the best. Or, to be precise, the debate about whether the American model will continue to outdo all comers, or instead be replaced at the top of the economic heap by a rival.

"Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism"helpfully moves the debate on from competing national models to the underlying structures that shape the relative effectiveness of different sorts of capitalism. Written by three economists, including 85-year-old William Baumol, arguably the leading thinker about the economics of innovation since Joseph Schumpeter [an Austrian economist of the first half of the 20th century], it identifies four main varieties of capitalism.

1. State-guided capitalism, in which government tries to guide the market, typically by supporting certain industries that it expects to become "winners".

2. Oligarchic capitalism, in which the bulk of the power and wealth is held by a small group of individuals and families.

3. Big-firm capitalism, in which the main economic activities are carried out by established giant enterprises.

4. Entrepreneurial capitalism, in which a major role is played by small, innovative firms.

The only thing that all four of these models of capitalism have in common is that they recognize the right of private property ownership.

Nor is there any single country that has exactly any one of the models described; in most national economies there is some blend of at least two. Moreover, the blend changes over time, and with it, the performance of the economy. Less than two decades after the fall of communism, Russia is already moving rapidly from oligarchic capitalism to an authoritarian state-guided capitalism.

What works best, argue the authors, is a mix of big-firm capitalism and entrepreneurial capitalism. And this happens to describe America's economy during the past 20 years, during which h time it has reversed its seemingly inevitable long-term decline and delivered a "productivity miracle".

The possibility of change is at the heart of "Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism". The authors are skeptical—for the most part, plausibly—of claims that the growth rates of economies are largely predestined by culture or geography, as books such as "The Wealth and Poverty of Nations"by David Landes or Jared Diamond's "Guns, Germs and Steel"suggest. There are no quick fixes, but over time the right policies can make a big difference, as can the wrong policies.

The authors argue that continental Europe and Japan, currently dominated by big-firm capitalism, can increase the role of entrepreneurial capitalism—perhaps, ironically, by learning from the incremental approach to reform of the Chinese government. And America, they say, is in danger of stifling its own entrepreneurial capitalism through the same increased regulation and risk-aversion that led to the dominance of big-firm capitalism in America in the 1960s and 1970s. If so, it risks losing its capitalistic crown, not as a result of any external threat, but through its own fault. [75]

Another Prescription for Better Capitalism-Restore Dynamism

A broader, more elemental perspective on economic woes comes from Professor Edmund Phelps of Columbia University, who is also director of its Center on Capitalism and Society. [76] Dr. Phelps' is a Nobel laureate; he was awarded the economics prize for work he did regarding unemployment and microeconomics.

His 2013 book, Mass Flourishing: How Grassroots Innovation Created Jobs, Challenge and Change, presents a wide-ranging assessment on what leads economies to thrive. His diagnosis of what's wrong with the economy is fundamental and delivered in a genteel manner; he strikes me as a mild mannered version of the Howard Beale character in the movie Network (mentioned in in chapter one)…but with a Nobel Prize.

Professor Phelps emphasizes the importance of dynamism—the willingness and capacity of an economy to innovate—a quality he says that has been in decline for decades for two reasons. The first is a rising hostility to what he calls "modern values."The second is movement away from a modern notion of the Aristotelian concept of the "good life"and toward a self-destructive fixation on money-making and materialism.

Before elaborating on his thesis, let's get his politics out of the way. Some of what he says appeals to the political left and some of it is off-putting to them. The same is true for those on the political right. His view is disorienting to anyone who views problems and solutions through a political prism. In part, because both ends of the spectrum benefit from what he sees as a key problem—corporatism. Its an uncommon word that refers to the control of a state or organization by large interest groups. Phelps sees the Democratic Party pursuing corporatism that goes well beyond the New Deal or Great Society. He despairs at the Republican enthrallment of "traditional values", values that suppress individual self-expression, which he associates with a rise in materialism and a desire to amass wealth. He also wants to move beyond the superficial argument that freedom will return economies to those of the past. [77]

There is pervasive use of "modern"in Mass Flourishing ; modern era, modern society, modern economies and modern values, attitudes and beliefs. This word generally means relating to the present time or using recent ideas or designs but Phelps embraces another meaning—the untraditional, novel, disruptive or even subversive.

The tableau Phelps works with begins in antiquity and he says "some ideas that we think of as modernist existed in ancient times but were not widespread or they were driven out in the middle ages."He relies on Jacques Barzun's 2000 book, From Dawn to Decadence, to mark the beginning of the modern era around 1500, with the start of the European Renaissance. And, he refers to 1815, after Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo, as the start of modern society . In his 1991 book, The Birth of the Modern, Paul Johnson argues that "the matrix of the modern world was formed then: the U.S. became a global power, Russia expanded rapidly, Britain penetrated the Middle East, Latin America threw off Spain's yoke, and an international order which would endure for a century took shape." [78]

Modern economies are what emerged first in Britain, then America, followed later by France and Germany. Somehow, the economies of these nations developed dynamism —the appetite and capacity for indigenous innovation (i.e., homegrown, as opposed to copied from another country). What followed was a breakout of prosperity that fired imaginations and transformed working lives. The emancipation of women and abolition of slavery widened the flourishing. The creation of new methods and new products was driven at least as much by business people—entrepreneurs, financiers and marketers—and pioneering end-users as by scientists. In talks about his book, Phelps says "The epic story of the West is the development in the 19th century of a mass prosperity the world had never seen and its near-disappearance in one nation after another in the 20th." [79]

Modern values, Phelps writes, "are the attitudes that began to be formulated in the modern era, accelerated with modern society and are the foundation of a modern economy. They remain prevalent in Western nations, even though they differ significantly by country."Examples of modernist values are:

- Thinking and working for yourself;

- Self-expression;

- Readiness to accept change caused or desired by others;

- Eagerness to work with others;

- Desire to test one's self against others, thus to compete; and

- The willingness to to take the initiative, thus go first.

"Modern attitudes are the desire to create, explore and experiment, the welcoming of hurdles to surmount, the desire to be intellectually engaged, and the desire to have responsibility and to give orders. Behind these desires is a need to exercise one's own judgment, to act on one's own insights, and to summon up one's own imagination. This spirit does not involve a love of risk. It is a spirit that views the prospect of unanticipated consequences that may come with voyaging into the unknown as a valued part of experience and not a drawback. Self-discovery and personal development are major vitalist values."

"Modern beliefs include some distinctive ideas about what is right; the rightness of having to compete with others for positions of higher responsibility, the rightness of greater pay for greater productivity or responsibility, the rightness of orders from those in responsible positons and the rightness of holding them accountable, the right of people to offer new ideas, and the right of people to offer new ways of doing things and to offer new things to do. All this stands in contrast to traditionalism with its notions of service, obligation, family and social harmony." [80]

Phelps says Western nations lost half or more of their dynamism in the 20th century: Britain and Germany in the 1940s, France in the early 1960s and America in the 1970s. He is skeptical the ability of the technology sector to raise the economy because its financial benefits are concentrated geographically, like in the San Francisco Bay area, and the revenues from many such innovations are insubstantial. What's needed, he believes, is an approach that has broader impact on more sectors of the economy.

Mass Flourishing identifies institutions and policies that block innovation; short-term perspective in big business and finance, under-taxation that gives people inflated perceptions of their wealth and a minefield of patent and regulatory risks. But Phelps says a more fundamental problem is that the desire to innovate has been dampened by waning belief in modern values and a rise in traditional values. He advocates a re-embrace of modern values because they encourage the innovation that people need in order to thrive and when they thrive, economic output and satisfaction are likely to improve.

The book defines innovation as new knowledge that leads to new practices. Phelps points out that scientists and engineers tend to view innovation as new knowledge, assuming that it will lead to new practices. Economists view the new knowledge and its adoption as two different phenomena. Thus, he recognizes the importance early users have in economic innovation. [81] Alternatively, he makes the point by saying that innovations (an innovative society) depends on a system—innovative people and companies are just the beginning. There must be people with the ability to judge well whether to attempt to develop or to finance a new thing. And, once the new thing its developed, whether it is worth trying. Theses ideas are in these conceptual equations.

Innovation = New Knowledge that Leads to New Practice

New Practice = Origination of New Thing (concept & development) + Pioneering Adoption

Embrace of New Practices = Dynamism = Modern Society = Modern Economy

Let's return to Phelps' use of the word dynamism, a quality that leads to innovation. He describes it as the willingness and capacity to innovate, leaving aside current conditions and obstacles. He points out that the distinction between innovation and imitation is fuzzy. That nations historically relied on their own ability to innovate (indigenous innovation), but, increasingly, they adopt innovation originated elsewhere (exogenesis innovation).

Phelps uses this insight to distinguish economic dynamism from economic vibrancy, which is the alertness to opportunities, a readiness to act. Then, he states that the economic growth rate is NOT a useful measure of dynamism . In fact, an economy with little or no dynamism may regularly have the same or better growth in productivity and/or real wages that a dynamic one has. How? Partly, by trading with a dynamic economy, but, mainly, by being vibrant enough to imitate the new practices of a dynamic economy. In fact, an economy with low dynamism might for a time show a faster growth rate that a modern economy does with its high dynamism.

Interestingly, he suggests three ways that the effect of dynamism in an economy might be measured; consider the forces and facilities that are its inputs, estimate its output and assess circumstantial evidence of its strength. [82] These approaches are below.

1. Consider the strength of the forces and facilities that are its inputs

- Drive to change things

- Talent to change things

- Receptivity to new things, and

- Institutions that enable change

2. Estimate its output

3. Assess circumstantial evidence

- New company formation

- Employee turnover (i.e., higher turnover = higher dynamism)

- Turnover in the list of large companies in an economy

- Turnover of retail stores

- Mean average life of universal product codes (UPC bar codes)

So, if an economy with little or no dynamism can have growth that equals or even exceeds one that has, and, if economic dynamism risks disruption, why encourage it? Phelps argues persuasively that it is positively correlated with growth while acknowledging that dynamism can result in bad luck. But he emphasizes that the central reward of a modern economy is that its participants have the opportunity to pursue the Aristotelian concept of the good life. Conceptual, the notion is expressed here:

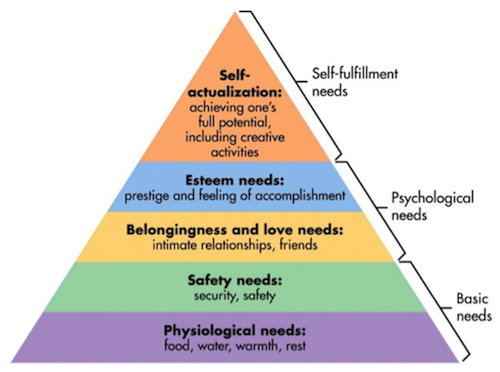

Singer Tony Bennett popularized a song about romance called The Good Life that includes the line "It's the good life to be free and explore the unknown."That reflects a sentiment that Phelps says Aristotle had in mind about what made a life fulfilling and, by extension, what makes an interesting job satisfying. For him, the good life as something that people would choose once their need for essentials were comfortably met. A similar notion was expressed by 20th century psychologist Abraham Maslow in his theory of human motivation, illustrated in the diagram below. Maslow's hierarchy of needs has self—actualization-a form of the good life—as the highest need, sought once other lower ones are satisfied.

Because some money making is forced on society, Aristotle likely felt that the good life was a luxury for the elite and not easily in reach by the less fortunate, but Phelps believes that the good life was accessible to those at the bottom rungs of society. He points out that there is little reason to conclude that slaves lacked desire or capacity for the highest good and that Aristotle's own teacher, Plato, may have been sold into slavery.

Mass Flourishing highlights the thoughts of many thinkers over the ages on variations of what brings people the greatest satisfaction in life. The most succinct expression of this doctrine of "vitalism"may be "to boldly go,"NASA's motto in the early days of the project to go to moon (and in the Star Trek television show). Phelps' adds this:

"The difference between the pragmatist take on the good life and the vitalist take is striking. The word 'hurdle' is in the lexicon of both schools, but hurdles come up in contrasting ways. In the vitalist view, people are looking for hurdles to overcome, problems to solve: if you do not happen to meet any, you change your life so that you start meeting them. In the pragmatist view, people encounter hurdles in the course of being pragmatic-of working in an industry or profession that seems to offer the best prospects of success. Pragmatists do not specify what human kind wants to succeed at. They only say that, whatever a person's career is aimed at, the person—unless very unlucky—will meet innumerable problems and solve a great many of them. Their engagement in problem solving is an intellectual side of the good life. The resulting mastery is another part of the good life: the part called achievement ." [83]

Phelps argues that "vitalism is enjoying a revival after decades of pragmatism,"then considers how Aristotle might apply eudaimonia, ancient Greek for happiness or flourishing, to contemporary times. He cites research "that many Americans want to feel embarked on a mission to make a difference ." [84] So, what constitutes a vibrant one? Phelps posits that:

"A society seeks and builds an economy to provide mutual benefits for its citizens. So, as a life in pursuit of the highest good, or benefit, is termed by Aristotle the 'good life,' an economy enabling people's mutual pursuit of the highest good may be termed a good economy . An economy is good if and only if it permits and fosters the good life." [85]

What can be done to restore economic dynamism? Phelps sees an important role for government at all levels, provided it rescinds old interventions at least as actively it initiates new ones. He also makes the following recommendations [86]

- Government must be aware of the importance of dynamism in a modern economy.

- To take well-judged actions, governments must have a sense of the way forward. They have to have an elementary understanding of how the business sphere of a well-functioning modern economy generates dynamism. It is not mechanical: it is organic. It is not an ordered system: it is topsy-turvy. Legislators and regulators should ask of every bill or directive: "How would it impact the dynamism of our economy?"

- Policy makers should disabuse themselves of the notion that economic growth is increased by policies that stimulate some industries over others through subsidies, mandates, private-public partnerships or government-sponsored enterprises.

- Shrink or terminate policies that promote a corporatist economy; much special interest legislation exists in the form of tax deductions, exemptions and carve-outs. "The U.S. tax code runs to 16,000 pages. The French have a tax code with only 1,900 pages." [87]

- Stop paying CEOs very high short-term salaries as this induces short-term thinking. Corporations should not be able to use their capital for golden parachute payments.

- Don't allow mutual funds to threaten a CEO with dumping her company's stock if she doesn't fix her attention on hitting the next quarter's earnings target.

- Overhaul the banking industry to provide vastly more credit for innovative projects and start-ups. Specifically, restructure the behemoths into smaller units with narrower lines of business, leaving risky assets to markets with the appropriate expertise.

- Reexamine the ability of labor unions and professional associations to inhibit innovation or restrict new entrants into markets.

- Reintroduce to secondary and higher education the main ideas of modern thought, such as individualism and vitalism (i.e. a creative and venturesome spirit).

Onward

The question of how to invigorate economic growth is a large one and it's easy to find an array of views on how to answer it.

The distinguished economists cited in this chapter are not ideologues and they straddle the macro- and micro-economic spheres. They share the idea that the weak U.S. economy calls for something different. Robert Litan and Carl Schram narrow their recommendations to immigration reform, improved access to capital, more rapid commercialization of university intellectual property and regulatory reform. Edmund Phelps' goes long and broad, making the case to restore the dynamism that leads to innovation.

The Fairshare Model is about improving access to capital for venture stage companies. Such companies play an outsized role in America's economic growth, its ability to engage in mutually beneficial trade with other nations and to create engaging, fulfilling jobs. It's also about fostering an innovative social compact between investors and workers.

Often, a risk assumed does not have a favorable outcome. Its the nature of things, but its the essence of being to assume risks. Venture stage companies are inherently risky. Entrepreneurs are more likely to fail than succeed. The cost to them can come from foregoing stable employment, loss of capital, increased debt and lost time. The struggle can fray personal relationships and create a stigma of failure. But still many try. Venture investors are more likely to lose money than make any, but there are many, including those who are non-accredited, who want to provide it. Many who have had success have also suffered losses; some who have had little or no success continue nonetheless. Early adopters of a technology often pay a price for being in the first wave, but they are willing to take the leap. A bad outcome can be the nature of things, but so is hope.

Dear Reader, I hope you see the potential benefit to the economy of making it easier to responsibly provide better access by entrepreneurial companies to Middle Class investors, and vice versa. That it is possible to view this activity apart from the prospect to make money--to see it as a pursuit of The Good Life. As an expression of support by investors to an obsessive entrepreneurial team with a quirky idea that is unlikely to generate a financial return for investors. They are all dreamers of what may be possible and their existence is a vital asset to the economy.

And if the investment doesn't pay off, so what? So long as the investor didn't invest more than he or she could afford to lose, didn't overpay and wasn't mislead, its possible that the investor was in pursuit of The Good Life. The lessons learned may make success more likely down the road.

A later chapter will discuss fraud. But for now, reflect on the how this activity could help the economy restore its innovative engine, strengthen its mojo (i.e., a power that may seem magical and that allows someone to be very effective, successful, etc.).

The next chapter explores the implications of the Fairshare Model for another macro-economic issue---income equality.

[68] At publication, Litan was vice president for research and policy, Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, and a senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution. Schramm was a visiting scientist at MIT and had been president of the Kauffman Foundation for a decade. Both are fellows of the Bush Institute.

[69] Better Capitalism, pages 5 to 6

[70] Better Capitalism, page 7

[71] The Importance of Startups in Job Creation and Job Destruction, by Tim Kane, page 2, http://www.kauffman.org/what-we-do/research/firm-formation-and-growth-series/the-importance-of-startups-in-job-creation-and-job-destruction

[72] Link to sketchbook http://www.kauffman.org/multimedia/sketchbook/kauffman-sketchbook-better-capitalism

[73] Better Capitalism, by Robert Litan and Carl Schramm, page 110

[74] From President Barack Obama's June 11, 2013 remarks on immigration reform"

[75] America still wears the crown, The Economist, Jul. 5, 2007, http://www.economist.com/node/9433839

[76] The website for the Center is http://capitalism.columbia.edu/

[77] Summarized from _______

[78] Publisher's description

[79] "Mass Flourishing: How It Was Won, Then Largely Lost", lecture delivered by Phelps Oct. 9, 2013

[80] The description of modern values, attitudes and beliefs are from Mass Flourishing, pages 98 - 99

[81] This underscores, Dear Reader, how critical buzz about the Fairshare Model is to its adoption by pioneering entrepreneurs.

[82] Mass Flourishing, page 21

[83] Mass Flourishing, pages 283-284

[84] Mass Flourishing, page 285

[85] Mass Flourishing, page 288

[86] These recommendations are in pages 316 to 324 of Mass Flourishing

[87] Mass Flourishing, pages 164-165

Karl M. Sjogren *

Contact Karl Sjogren is based in Oakland, CA and can be contacted via email or telephone:

Karl@FairshareModel.com

Phone: (510) 682-8093

The Fairshare Model Website

A native of the Midwest, Karl Sjogren spent most of his adult life in the San Francisco Bay area as a consulting CFO for companies in transition—often in a start-up or turnaround phase. Between 1997 and 2001, Karl was CEO and co-founder of Fairshare, Inc, a frontrunner for the concept of equity crowdfunding. Before it went under in the wake of the dotcom and telecom busts, Fairshare had 16,000 opt-in members. Given the rising interest in equity crowdfunding and changes in securities regulation ushered in by the JOBS Act, Karl decided to write a book about the capital structure that Fairshare sought to promote….”The Fairshare Model”. He hopes to have his book out in Spring 2015. Meanwhile, he is posting chapters on his website www.fairsharemodel.com to crowdvet the material.

Material in this work is for general educational purposes only, and should not be construed as legal advice or legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances, and reflects personal views of the authors and not necessarily those of their firm or any of its clients. For legal advice, please consult your personal lawyer or other appropriate professional. Reproduced with permission from Karl M. Sjogren. This work reflects the law at the time of writing.