The Fairshare Model: Chapter Five

Karl M. Sjogren

2015-04-10

By Karl M. Sjogren *

Chapter 5: Target Companies for the Fairshare Model

Preview

- Foreword

- The Appeal of the Fairshare Model

- Common Qualities

- Categories of Companies-Overview

- Feeders (a strategic category)

- Sidebar on the Cost of Being a Public Company

- Aspirants (a strategic category)

- Pop-Ups (a non-strategic category)

- Spin-Outs (non-strategic category)

- Rejuvinators (non-strategic category)

- Possible Variants

- Can One Tell What Category a Company Is?

- Onward

Foreword

What type of companies might adopt the Fairshare Model? This chapter contemplates five categories of companies that are likely candidates.

The Appeal of the Fairshare Model

As chapter three discussed, a conventional capital structure has strengths but it is beset with the valuation-related challenge. Increased awareness among public investors that they are the Next Guy for dicey IPO valuations is sure to create interest in an alternative approach, one that offers them a better deal. So, aside from public investors who are dissatisfied with their opportunities to invest in venture-stage companies, who else might like the Fairshare Model? What kind of companies might consider adopting it?

- Companies with poor access to professional venture capital.

- Companies who are unhappy with the deal structures offered by VCs or private equity funds.

- Companies who seek a competitive advantage to build and manage human capital

- Those whose management is attracted to the sensibilities of the Fairshare Model.

Common Qualities

Entrepreneurs who adopt the Fairshare Model for their company will share some qualities.

Surely, they will be confident that they can deliver the performance that investors expect. Those without such confidence are unlikely to adopt a capital structure that ties their wealth to performance. Possibly, the team will be overly confident; confidence is good, but no guarantee for investors. But would you rather invest in an overly confident company using a conventional capital structure or one that is willing to adopt the Fairshare Model?

Of course, those that choose the Fairshare Model may include companies that have trouble attracting capital. But that may be true for any public offering, regardless of whether the Fairshare Model or a conventional capital structure is used.

Some believe that a company that seeks capital from (unsophisticated) unaccredited investors is, by definition, desperate . That's because there is thought to be an abundance of (sophisticated) private capital available.

There is a measure of truth to this. Management at a company that has trouble raising capital is likely to be desperate. No money means no expansion, failure to launch, contraction or even demise. [43] The pressure may lead them to overstate their prospects or to understate or omit negative information in their offering documents. Securities regulators seek to minimize this, but no system is perfect.

Many, if not most, venture stage companies are desperate for capital at some point—even those with VC backing. That's because all such companies depend on outside capital—they do not generate enough cash from operations to sustain operations. And yes, there are VC-backed companies that struggle to find investors for a subsequent round. Some are desperate squared; desperate for capital and desperate to avoid a down round.

So, it's haughty and provincial to dismissively paint all companies that try to raise venture capital in a public offering as "desperate."It presumes that private capital is efficient in the sense that entrepreneurs with attractive opportunities find the capital needed. Geographically, that's untrue—VCs favor opportunities that ae near their office because there are many demands on their time. Industry wise, that's untrue-private venture capital tends to cluster around relatively few market sectors. They focus on opportunities that have the potential to generate at least a 30X return on investment (i.e., a $1 investment grows to $30 in value)—ignoring those that offer less or are more risky.

To pre-judge companies that seek capital from unaccredited investors as desperate demonstrates a world-view similar to the one satirized in an iconic New Yorker magazine cover, "A New Yorker's view of the world". Just replace Manhattan with a center of capital like Silicon Valley, NYC or DC. The buildings in the foreground represent opportunities that may generate $30 or more for every $1 invested in 3 to 5 years. Companies outside this neighborhood are on the other side of the Hudson River. Possibly, a nice place to go but "there's just so little time and so much to do here in NYC (or in Silicon Valley)!"

In passing, I'll note that private capital isn't reasonably available to management teams of all backgrounds. Graduates of colleges that a preponderance of venture capitalists themselves attended are far more likely to get funded. Also, companies lead by women and minorities are significantly underrepresented in VC portfolios.

My point is that VCs don't cover the universe of opportunity, and, a company that pursues a direct public offering is not inherently inferior to those backed by VCs. It's true that promising companies prefer VC backing but more of them will consider equity crowdfunding if the benefits of doing so become apparent. Besides, since average investors can't invest until a stock is public, it's a bit of a moot point to compare a VC backed startup to a startup that uses equity crowdfunding.

So, with all that, four characteristics likely to be common to companies that adopt the Fairshare Model are:

1. The entrepreneurial team will be confident in their ability to perform.

2. The company cannot attract private capital on terms that it is satisfied with.

3. The issuer is willing to treat IPO investors as venture partners, not just as the ultimate Next Guy at the end of a series of VC rounds.

4. Management perceives that Performance Stock will give them a competitive advantage when recruiting and managing their workforce.

Notice that there is no minimum level of revenue or profitability or net asset value. The ONLY requirement to have a public offering is to have investors willing to buy the stock. If you doubt that, think about biotech companies that have a Wall Street IPO—few have revenue. [44]

Before we proceed to the categories, I want to make two points about how any company that uses the Fairshare Model will raise capital, whether it uses a broker-dealer or DPO.

First, all will target investors who have an affinity for what it seeks to accomplish, where the company is located or who is running the company. In other words, they will seek investors who are motivated by more than the potential to make money; those who want a reason to invest that isn't dependent on a financial payoff (i.e., a social benefit). So, all issuers will seek buy-and-hold investors--the type who knows the odds of failure are high and nonetheless supports the effort. The affinity may be based on the industry, technology, goal or the geographic location. It may be based on the management team. For some, it will be based on the Fairshare Model itself! That is, there will be investors who are inclined to invest in any company that adopts the model.

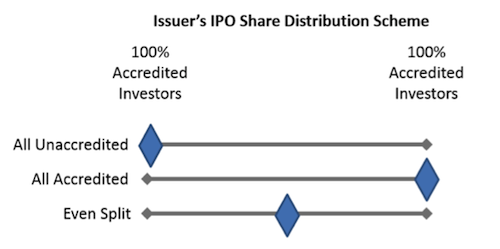

Second, the Fairshare Model is a loose construct for companies with respect to how they distribute their new shares. There will variation based on the needs of the issuer. At one extreme, the issuer will target only unaccredited investors. At the opposite extreme, the issuer will target accredited investors for the entire offering. An issuer might do this to avoid having the offering open too long. Wealthy investors would have the opportunity to sell off shares to unaccredited investors in the secondary market.

It may surprise you that this is a contemplated option because wealthy investors get all the IPO shares while the Fairshare Model aspires to provide opportunity for average investors. But if unaccredited investors are slow to buy, issuers will be wise to sell any available shares to accredited investors in order to minimize the duration of the offering. The Fairshare Model is a practical form of idealism. Those who matter most to me are the IPO investors because they supply the issuer with capital. The needs of the issuer come next in priority and those of secondary market investors come after that. In this effort to balance interests, there is a clear pecking order.

A hybrid distribution plan with a mix of accredited and unaccredited investors is likely to be the most popular, especially as the total offering size grows.

Categories of Companies-Overview

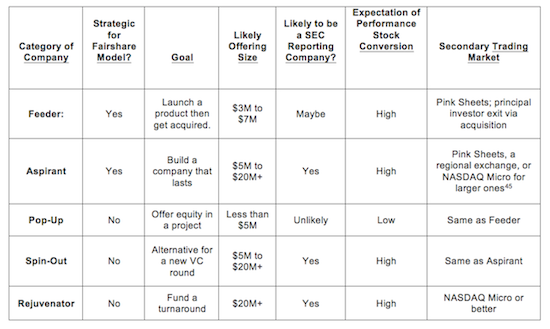

So, what types of companies might adopt the Fairshare Model? Five categories are summarized in the following table and discussed in the pages ahead. Two of them are strategic for the Fairshare Model; I refer to them as Feeders and Aspirants. If they were race cars, a Feeder is a dragster that goes down a straight track as fast as it can—the race is seconds long. An Aspirant is a Formula One car that races for hours over a course with twists and curves. There are three non-strategic categories as well, Pop-ups, Spin-outs and "Rejuvenators."

The table shows the goal of each and the likely size of their public offering. For example, Feeders are likely to have offerings between three and seven million dollars and Rejuvenators are likely to raise more than twenty million dollars.

Two adopters of the Fairshare Model may decide not to be a SEC "Reporting Company." [46] Such an issuer must file periodic shareholder reports with the agency (i.e. 10-Q or 10-K). In order to minimize overhead cost of this, Feeders and Pop-Ups might disclose in their offering document that they don't intend to be a reporting company. Other categories of issuer are likely to make it a priority to be one.

Except for Pop-Ups, all categories will have high expectation of Performance Stock conversions. The categories will vary in the secondary trading markets for their stock. The Pink Sheets (a/k/a Bulletin Board), where liquidity is slim to none will be the default for small offerings.

Feeders (a strategic category)

Feeder fish inspire this moniker. Aquariums use them as food for the larger fish in their collection; big fish eat little fish. The Feeder category is strategic for the Fairshare Model because these companies will most easily reap its advantages and successes here will lead others to adopt it.

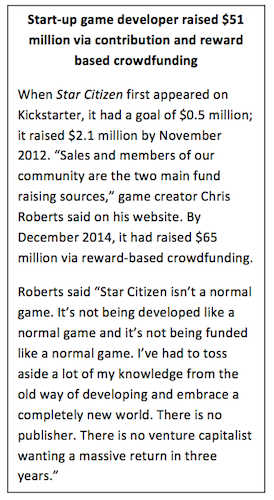

A Feeder seeks capital to develop a product/technology that other companies will pay a premium for. Ultimately, its strategy is to be acquired at a healthy price. For entrepreneurs, this strategy avoids the cost, risk and stress of building the infrastructure needed for the long-term (i.e., employees, facilities, computer systems). Feeders focus on the technology, building a product and proving demand. For investors, a Feeder can generate a return faster than a build-for-the-long-haul company. Here are a few indicators that Feeders are common:

- In a thirteen month period, Yahoo acquired twenty start-ups. [47]

- From its 2006 inception through mid-2013, Twitter made 31 acquisitions. [48] In April 2014, it acquired a year old company that had raised $1.5 million. [49]

- In August 2014, Samsung acquired SmartThings for $200 million. In 2012, SmartThings used rewards-based crowdfunding to raise $1.2 million from 5,700 backers (average $210 per person) to launch its product. It went on raise $16 million from VCs before Samsung bought it. [50]

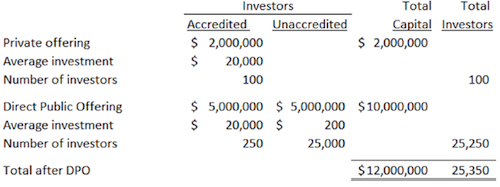

The Fairshare Model offers a Feeder an alternative to a VC round. Imagine a company raises $2 million from 100 angel investors who invest $20,000 each. It goes on to raise $10 million in a direct public offering where half comes from accredited investors and half from unaccredited investors in $200 allocations, as shown below.

As a result, there are about 25,000 investors, evangelists for the company's product, a few of whom may be able to generate interest by potential acquirers. A start-up can't have too many friends. By spreading its shares in this manner, this Feeder spawns interest in its success. By contrast, a competitor that relies on VC backing must spend capital to get such awareness. And, it can't spend enough on advertising to sustain the interest that our Feeder created by making it possible for target customers to own a piece of the action.

Is a $200 investment sufficient to move 25,000 shareholders to actively promote the interests of the Feeder? Yes, for two reasons. First, people like to have a team to root for and they favor those with whom they share an affinity. Second, this investment is at a wholesale valuation, not the retail valuation that the public normally gets. The retail valuation could easily be 5 times higher than what the Feeder sold it for (i.e., they got a $1,000 stock for $200). [51] There is a glee factor in that.

In this illustration, the holders of Investor and Performance Stock have an aligned interest-they want to be acquired. Say that there is an offer for $40 million. So, $12 million in equity has been raised; $2 million in the private round and $10 million in the public one. Subtract that from the $40 million offer and there is $28 million of appreciation. How should that be split between the two shareholder classes? Two charts that follow will illustrate scenarios.

Before looking at them, recognize that both classes of stockholders must agree on how much Performance Stock converts and this agreement will vary by company.

One approach will be to decide by prior agreement. That is, a formula in the issuer's incorporation document. [52] A simpler alternative is simply to require approval of any acquisition agreement by both classes of stock. After all, this will be required even if there is a formula. No approval means no deal, so, shareholder groups that don't agree invite the problems of divided government.

The U.S. had this from 2010 to 2014. Republicans controlled the House of Representatives and Democrats had the Senate and the Presidency. In 2013, the two legislative bodies could not agree on a budget to fund the government. No budget meant government shutdown. To pass one, they fashioned a clause to implement automatic, painful budget cuts (a/k/a sequestration) if they later failed to agree on how to implement the budget. The clause forged approval for a high-level budget when there was no agreement on how to enact it.

If the Investor and Performance Stock don't agree on how to share a buyout offer, they face a comparable situation. They lose the deal and they must agree on how to raise any capital that is needed to continue operations as an independent company.

In this illustration, should there be an impasse, the acquirer might make separate offers for the Investor Stock and the Performance Stock, with employment agreements to enough employees to get Performance Stock approval. In other words, there may be a way to get the deal done when there is a lack of goodwill among shareholders. If not, the acquirer may come back with a lower price when the company is desperate for new capital.

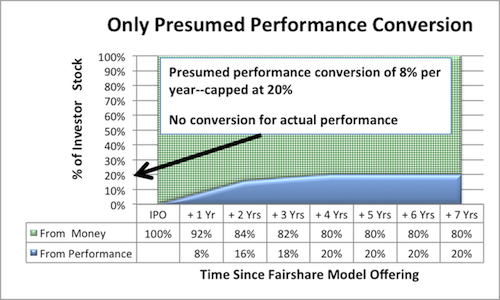

In both scenarios that follow, there is prior agreement that Performance Stock equal to 2% of the Investor Stock outstanding as of the IPO converts each quarter (i.e., 8% per year). It is the deal that the company described in its offering documents; IPO investors got a low valuation in exchange for agreeing to this "presumed performance."This makes Performance Stock an effective incentive because employees can count on it. It also simplifies the issues of defining and measuring performance. [53]

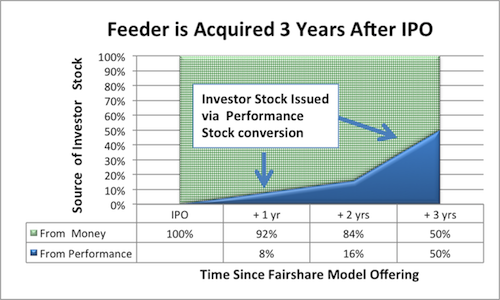

The chart below has the first scenario; the $40 million acquisition takes place three years after the IPO that raises $10 million. The green grid area shows the proportion of Investor Stock outstanding at the close of the IPO . The solid blue area is the proportion of Investor Stock that results from Performance Stock conversion. Note how the origin of Investor Stock shifts over the three years.

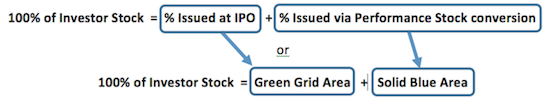

Of course, the number of shares of Investor Stock increases when there are conversions, but the chart does not measure that. Instead, it maps the two variables in this conceptual equation for the totality of the Investor Stock, assuming there has only been one offering.

In the chart, a year after the IPO, the portion of Investor Stock from Performance Stock conversion is 8%. [54] Two years later, it's 16%. The acquisition offer comes three years later, so, more than 24% will convert (year two 16% plus 8%) because Performance Stockholders have delivered more than the nominal presumed performance. Here, the two classes of stock agree to a 50-50 split, so, enough Performance Stock converts to make the cumulative conversion 50%. At close of the deal, all unconverted Performance Stock is cancelled.

At the end, the shares the company sold for $12 million share half the $28 million in appreciation or $14 million. Those who had Performance Stock share the other $14 million. Not bad for three years work. [55] In all likelihood, the employees are richer than if the company had raised the $10 million from VCs instead of the IPO.

Why would this be so? Because professional investors need a bigger payoff than angel investors and average investors. VCs demand a higher return because their limited partners---those who invest in their funds---expect an attractive return and the general partners want a payoff too.

Aside from the financial payoff, the entrepreneurial team enjoyed more control over the company than it would have had VCs provided the $10 million. Their voting power is based on Investor Stock they earned for pre-IPO performance plus the Performance Stock that they control. For entrepreneurs, the ability to chart and hold a course can be at least as important as a financial payoff. [56]

The company's angel investors benefit in this example too. They invested $2 million and didn't have to invest more because public investors did. [57] The IPO money was on terms that were friendlier than a VC would offer (e.g., no dividend, management fee or liquidity preference). Plus, the angel investors had a liquidity option during the three years after the IPO; they could sell some or all of their shares, something they could not do if the company had been private.

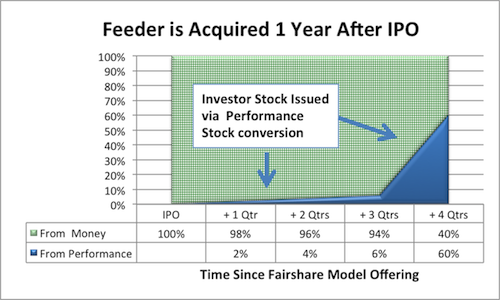

In the second scenario, the $40 million acquisition offer comes 1 year after the $10 million IPO . The only difference is that the offer comes two years earlier. Arguably, Performance Stockholders deserve more of the $28 million appreciation because they delivered it much faster. Another argument for this is that public investors got a lower IPO valuation than they would have had the company used a conventional capital structure. Now that the true value is apparent, it is time to more fairly divide it.

In the chart below, the horizontal axis shows time in four quarters, not three years as in the last one. Like before, presumed performance results in quarterly conversions equal to 2% (8% per year) of what is outstanding after the close of the IPO. As a result, converted Performance Stock accounts for 2% of all Investor Stock one quarter after the IPO, 4% after two quarters and 6% after three. It would be 8% at the end of four quarters but the acquisition offer changes that. Now, the question is "how to divvy up the $28 million in appreciation?"

Here, the two classes of stock agree that the Performance Stock deserves 60% of the Investor Stock issued as of the IPO. So, 40% or $11.2 million of the $28 million goes to the Investor Stock and 60% or $16.8 million goes to the Performance Stock. Again, any unconverted Performance Stock is cancelled upon close of the acquisition transaction.

Take-away: companies with a Feeder strategy will be attracted to the Fairshare Model because its employees can earn more of the appreciation than VCs would allow.

Sidebar on the Cost of Being a Public Company

Before moving to the next category, Aspirants, let's touch on the expense of being a public company. Broadly, this is the duty to file public disclosures with the SEC about financial statements, significant changes in ownership, management changes and anything else that investors are likely to consider relevant to their decision to buy, hold or sell the company's stock. An issuer that complies with these requirements is a "reporting company". Stock exchanges will not a list the stock of an issuer that is not a reporting company but they can be traded in the swamp alternately known as the pink sheets, bulletin board or over-the-counter market.

To begin with, there is the cost to prepare and sell the actual offering. The more history to disclose, the more expensive it is to prepare the offering document. Since a start-up has little history, it has little to disclose. As a result, it can get an offering prepared for $20,000 to $60,000. Then, there is the cost to sell the offering. If a broker-dealer is hired, the commission will run 8% to 12%, plus other expenses. A major objective of crowdfunding is lower costs to raise capital.

The annual cost to be a small reporting company can easily run $400,000 to $800,000 when one considers legal, audit, investor relations, employees knowledgeable about SEC requirements and insurance premiums for director and officer liability. The JOBS Act reduces some obligations for small public companies, but the cost of compliance remains significant, regardless of the capital structure. Much of the cost is fixed in nature so it falls more heavily on a company that raises, say, $5 million than on one that raises $20 million.

These costs will be a concern for Feeders. Some will meet the requirements to be a reporting company but some will choose to not be one so that they can maximize the funds available for product development and operations. Hopefully, an issuer that takes the later route will disclose this intent in the offering document by saying something like this:

Your investment is a chip in a game of chance. The odds of a payoff are not good and they are not improved if we spend a significant portion of the money we raise from you to be a reporting company. To maximize the resources that we can apply to our product development and launch, we may elect to not be a reporting company-making it more difficult for you to find a buyer for your shares. Should we not be a reporting company, we intend to notify shareholders of business developments and actions that require their approval. If we are not a reporting company, Performance Stock conversions will be suspended and our directors and management pledge to not sell their Investor Stock until we have been a reporting company for 90 days.

Essentially, I offer for discussion two strategies for Fairshare Model issuers to deal with the costs of being a reporting company:

- Plan A: view the expense a cost of doing business; accept it and try to contain it.

- Plan B: don't be a reporting company but forewarn investors and don't allow insiders to acquire or sell Investor Stock while the condition persists.

Aspirants (a strategic category)

The Fairshare Model is designed for a company with what I call an Aspirant strategy. It aspires to build for the long-term. If it's to be a party to an acquisition, it intends to be the acquirer, not the acquired.

The metaphor for an Aspirant is a Formula One race car because it needs to maneuver through a more complex course over a longer period than a Feeder faces. That's a way to say that Aspirants will have a complex challenge of defining and measuring performance over a sustained period of time. Ideas for how to accomplish this will be a focus of the shake-down phase of the Fairshare Model—one that will involve lots of people.

A Feeder is strategic category for the Fairshare Model because its path to success is relatively simple; raise the money, build the product and decide how to divide the acquisition price. It's a limited test of the model. An Aspirant is a strategic category because it is full test of the model; how does an organization coordinate incentives for labor and capital in order to create competitive advantage? Given time and experience, a set of proven best practices will be identified for Aspirants. At that point, the Fairshare Model will be positioned to be adopted on Wall Street.

Compared to a Feeder, an Aspirant's two shareholder classes have a greater need to collaborate because adjustments to the conversion rules will be a way of life. How these groups view performance will evolve as the company and its environment does. Their ability to cooperate will be tested by external factors (i.e., economic conditions, market shifts, competition, availability and price of materials, etc.) and internal factors (i.e., leadership, employee turnover, disrupted plans, etc.). Changes in the composition of each shareholder class will also play a role; investors who buy their stock at the IPO will have a different perspective on performance than those who invest later. For all of these reasons, an Aspirant will face greater challenges than a Feeder.

On top of that, there will be variation based on industry, stage of development, geography, and personality. That's why there is much to learn from the shake-down phase of the Fairshare Model and the experience of early adopters. Nonetheless, some ideas can be sketched out now.

When defining performance for a start-up, revenue and profitably will be standard but possibly inadequate measures. Some may not have a product for a while. Important measures of performance like strategic partnerships, design-in agreements, securing distribution and even customer orders may take a while to be expressed as revenue or profit. Cash burn rate is a vital operational measure but potentially difficult for setting conversions. The same could be said for non-financial criteria such as product release, quality, market penetration and growth in customer base. Non-traditional measures of value-creation such as environmental impact, job creation and awards are similarly challenged.

You might think that "performance"would be relatively easy to define and measure, but it is not. Think about things that are widely shared aspirations—peace, justice, fairness, quality, or effectiveness. How easy is to come up with a shared definition? Think about things that are generally viewed in a negative light—it may be slightly easier to find a consensus definition for harm, injustice, unfairness and so on. Often though, we are like U.S. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart when he issued an opinion in 1964 on whether material was pornographic. He said that he would not attempt to define what the word meant "but I know it when I see it."When it comes to defining performance, many feel similarly, which presents a significant challenge for the Fairshare Model—can holders of Investor and Performance Stock agree what they see and what it is worth?

That said, I think any definition of performance should include the raise of additional capital on favorable terms. Funding operations is the most important task for a venture-stage company for it is kaput if it fails to do so. Arguably, another measure of performance should be the market value of the Investor Stock. If it climbs, one can infer performance. But this logic has limits—should one infer a lack of performance if the stock price drops?

The difficulty of defining performance makes a case for presumed performance as a function of time. This is what most employee stock option plans do—the kind that are standard fare for technology companies and others. Employees get an opportunity to buy stock in the future at the current price. This right or option typically vests, or becomes exercisable, over time. A company using the Fairshare Model might use this approach---have conversions based on presumed performance-while also allowing for additional, performance-based conversions.

Such a hybrid conversion criteria keeps the Fairshare Model attractive for IPO investors, the company and its employees. Investors get a deal on the Investor Stock—a deep discount from what the valuation would be if the issuer uses a conventional capital structure. They know that a baseline amount of Performance Stock will convert each quarter. They weigh its dilutive effect on percentage ownership against the prospect that the Investor Stock will rise in price, then sell or hold their shares. New investors will have access to the same information and make a similar assessment. The appeal for the issuer and its employees is that Performance Stock is likely to be an effective tool to recruit and motivate desirable employees.

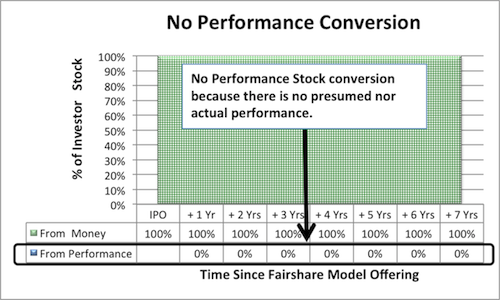

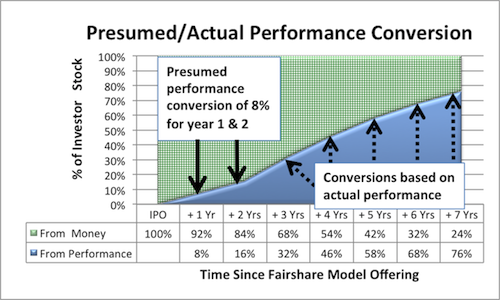

There is plenty to think about on this topic. The following charts illustrate three basic scenarios over a seven year period. The first assumes no Performance Stock conversion. The second assumes presumed performance up to a capped level. The third has presumed performance for two years and strong actual performance thereafter. Collectively, they provide a range of outcomes that could apply to an Aspirant, depending on how performance is defined and delivered.

The following chart illustrates no presumed or actual performance—the most adverse scenario for employees. Metaphorically, this Formula One race car had fuel (cash from the IPO) but it didn't complete a lap of the track. Bad car, bad driver or bad weather—whatever the reason(s) it turned out to be a dud. So, only those who pay money for shares or earn them with pre-IPO contributions have Investor Stock.

This presents an interesting hypothetical. What might happen to such a company when it is about to run out of money? The basic outcomes are:

1. New capital is raised.

2. The company is acquired. [58]

3. The company dissolves.

Each outcome has potential legal issues involving the respective rights of the Investor Stock and Performance Stock. But remember, this book's purpose is simply to create interest in the Fairshare Model, not provide a how-to guide. If there is enough to get the entrepreneurial community excited, the shake-down of the model will address ideas for how Performance Stock might work in these scenarios and they will be tested by early adopters.

Bear in mind that a conventional capital structure has to deal with the three outcomes too.

The following chart illustrates a scenario with presumed performance conversions for the four years following the IPO. After that, conversions require actual performance…but there is none.

Note that the time scale on the horizontal axis covers eight years, the IPO and the seven successive years. The presumed performance is what it was in the two previous scenarios, 8% per year of the Investor Stock outstanding after the IPO (or 2% per quarter), up to 20%. Here, the conversions stop after the cumulative percentage is 20%, four years after the IPO. It doesn't go higher because actual performance the fourth year is insufficient to trigger additional conversions.

Again, this is a conceptual example. Should the annual conversion rate and/or the maximum for presumed performance be different than modeled here? These are questions to be discussed!

Just like the prior charts, this one shows the origin of the composition of Investor Stock. It says nothing about who owns the shares. That's because anyone with Investor Stock can trade it.

Also, the chart does not illustrate the effect of issuing additional Investor Stock for more capital (or to acquire another company).

The third and final Aspirant chart is below—it's a blend of assumed performance and strong actual performance. There are two years of presumed performance conversions using the same 8% per year (2% per quarter) assumption as in the last scenario. But look at what happens three years after the IPO. The cumulative conversion is 32%! If the annual 8% factor was applied, the cumulative conversion would be 24% (3 years times 8%). But, the cumulative conversion is 32%, which means the year three conversion was 16% (32% minus 24%). Double the rate in the first two years!

The reason for the increase in year three is that actual performance exceeds the minimal presumed performance. And not just in year three! In the fourth year, the cumulative conversion from performance is 46%, so, the conversion was 14% that year (i.e., 46% minus year three's 32%). In year five its 12% (i.e., 58% minus year four's 46%). In year six its 10% (i.e., 68% minus year five's 58%). In year seven its 8% (i.e., 76% minus year six's 68%). This scenario could describe a company that spends the two post IPO years to develop its product then has a spurt of accomplishment that later tails off.

Starting in year three, take note of the cumulative percentage of Investor Stock that results Performance Stock conversions. The year three 32% is on the high end for what happens in a VC financed deal. But, it climbs to an unheard of 76% at the end of year seven! Recognize that some employees—founders and initial employees—have Investor Stock at the IPO (i.e., what's in the green grid area) for pre-IPO performance. The conclusion? An entrepreneurial team that adopts the Fairshare Model can wind up with more ownership than they will when VCs finance their company, provided they perform as their Investor Stockholders expect.

Like the two preceding charts, this one assumes that the company does not issue new Investor Stock. If it does, new investors are sure to buy in at a higher valuation. As a result, all owners of Investor Stock are happy, regardless of whether they bought their shares or earned them via performance.

The range of possible scenarios is beyond the scope of this book. It will take time to identify the Dos, Don'ts and Gotchas that may be important for an Aspirant. One thing is certain, however, the CEOs of Aspirants will have superior ability to communicate, inspire and manage. They will have keen insight into human behavior and group dynamics. They will also be able to strike a balance between their ego and willingness to be accountable to both classes of shareholders.

What works at one company may not work at others. Indeed, there will be variation based on industry, stage of development and geography (i.e., what works in Texas may not work in California). There will also be legal, tax and accounting issues that all issuers must address. The good news is that there will be legal, tax, financial and organizational specialists who are eager to help. And, importantly, the benefits promise to exceed the costs of making the model work.

Pop-Ups (a non-strategic category)

The name "Pop-Up"is inspired by pop-up stores, those that lease space for a few months. The landlord rents space on a short term basis while it waits to secure a long-term tenant or to do something else with the vacant space. The store wants a place to conduct business without a long-term lease. In the U.S., retailers who specialize in Halloween goods pop-up in September then go away in November. Such activity has gone on for decades but the term "pop-up"is of recent vintage. It reflects rising interest in entrepreneurship; an opportunity for entrepreneurs to see if might be on to something.

In the context of the Fairshare Model, a Pop-Up is a company that sells stock to the public to fund a project. The project might be a product, a movie, a game or an oil well. It might be a cause, like an effort to fund research, improve a city, agricultural practices…use your imagination. At present, this type of money is raised via donation or advance payment for the product that will be produced with the money. Crowdfunding sites are often used. The difference here is that people who "invest"in a Pop-Up get more than a good feeling for their money—they get stock.

From an investor perspective, a Pop-Up has dubious commercial viability in the sense that it will need money later and questionable whether others will provide it. From an entrepreneurial perspective, a Pop-Up is a bud of hope, an indication that investors share the sense of what might be possible…an Aspirant, or at least a Feeder.

So, investor and entrepreneur share a space—a view of the worthiness of the project—but not necessarily a perspective on the prospect for financial reward. That is, the backers may be willing to support the project without equity. If they get stock, they might donate more…its hard to say; they may just feel better about the donation.

Pop-Ups are not a strategic category for the Fairshare Model because they are unlikely to be acquired or become a reporting company. As a result, their performance is unlikely to generate a financial return for shareholders, whose money is better characterized as a contribution than an investment.

Spin-Outs (non-strategic category)

A Spin-Out is company that has raised capital from a venture capital fund but is not a good candidate for another. VCs refer to these types of investments as the living dead or zombies. To apply a baseball analogy, they are a first or second base hit in a game where a home run or triple is the goal.

The Fairshare Model should interest VCs because it offers the opportunity to spin-out such companies in their portfolio (i.e. public investors fund the next round), which allows them to distribute shares in these companies to their limited partners (i.e., institutional and wealthy individual investors). These investors would get Investor Stock and, possibly, Performance Stock as well. The combination would provide limited partners with liquidity plus an upside if the company performs well.

Spin-Outs are a non-strategic category for the Fairshare Model because it will not develop unless and until the model works for Feeders and Aspirants. Time and experience are not the only barriers to adoption; Spin-Outs mess with two elements of the VC model.

The first is the idea that public investors should pay a high valuation for a promising story. VCs are accustomed to seeing high valuations for potential successes —this precept is expressed in private rounds, acquisitions and IPOs. VCs clearly agree with the valuation ideas behind the Fairshare Model—they insist on them in their own deals—but some of them have a problem with the idea that public investors should be able to adopt them too. Some will see risk to offering shares in a VC-backed enterprise at low valuation. Others will think that it is crazy to offer the public a low valuation on one that has good potential. A similar sensibility once led retailers of brand-name goods to eschew discount stores. But premium outlet stores demonstrate that there is a way to maintain retail pricing in traditional stores and discount pricing elsewhere. So, I don't doubt some VCs will see potential in the Spin-Out strategy.

The second element in the VC model threatened by a Spin-Out strategy is the relationship that a fund's general partners have with their limited partners---those who provide the capital to invest. [59] If VCs utilize a Spin-Out strategy, it might invite scrutiny of general partner compensation.

Nonetheless, some VCs will explore Spin-Outs— if Feeders and Aspirants have good results. The reason is suggested in a 1997 book by Clayton Christensen that has been read by virtually every VC, The Innovator's Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail . Christensen describes how new entrants in an industry attack the dominant players from the low-end of the market, offering products that are cheaper and/or better in quality, design, etc. For instance, somnolence on the part of U.S. and European auto makers created an opening for Japanese manufacturers in the '60s and '70s—they ignored the low end of their markets. Korean automakers later adopted a similar strategy to take market share from American, European and Japanese companies.

Christensen's book provides examples in computers, steel and even milkshakes. Below is an excerpt from a 2013 interview he had with Jeff Howe of Wired that discussed a 1996 meeting he had Andy Grove, then CEO of Intel Corporation about disruptive innovations. [61] [Italics added for emphasis ]

Clayton Christensen: You could see how, in each generation [of computer disk drives], an established company would start focusing on bigger, more powerful disks for the top end of the market and then just get wiped out when the lower end of the market found a way to make smaller, cheaper disks, even though those had lower profit margins. It made my thesis. Smart companies fail because they do everything right. They cater to high-profit-margin customers and ignore the low end of the market, where disruptive innovations emerge from.

Jeff Howe (Wired): Is this around the time that Intel CEO Andy Grove heard about your work?

Christensen: This was before the book came out. I'd published two papers on my theory, and a woman who worked in the bowels of Intel's engineering department went to Andy and said, "You have to read this article. It says Intel is going to get killed."I hadn't even mentioned Intel, but the implications were there. So Grove called me up, and he's a very gruff man: "I don't have time to read academic drivel from people like you, but I have a meeting in two weeks. I'd like you to come out and tell me why Intel's going to get killed."It was a chance of a lifetime. I showed up there. He said, "Look, I'll give you 10 minutes. Explain what you think of Intel."I said, "I don't know anything about Intel. I don't have an opinion. But I have a theory, and I think my theory has an opinion on Intel."I described the idea of disruptive innovations, and he said, "Before we discuss Intel, I need to know how this worked its way through another industry, to visualize it."So I described how mini mills killed off the big steel companies. They started by making rebar cheaper than the big mills did, and the big mills were happy to be rid of such a low-margin, low-quality product. The mini mills then slowly worked their way upward until there was nothing left to disrupt.

Howe: What did Grove say?

Christensen: He cut me off before I could finish. "All right. I got it,"he said, and then he described the whole thing. Instead of the mini mills, there were two microprocessor companies, Cyrix and AMD, making cheap, low-performance chips. Grove says, "What you're telling me, Clay, is that we have to go down and kill them, set up our own business unit, and launch our own low-end competitor." I didn't say anything. I wasn't going to be suckered into telling Andy Grove what he should do with Intel. I knew nothing about semiconductors. Instead of telling him what to think, I told him how to think.

Howe: What did Intel wind up doing?

Christensen: They made the Celeron Processor. They blew Cyrix and AMD out of the water, and the Celeron became the highest-volume product in the company. The book came out in 1997, and the next year Grove gave the keynote at the annual conference for the Academy of Management. He holds up my book and basically says, "I don't mean to be rude, but there's nothing any of you have published that's of use to me except this."

The Fairshare Model is a disruptive innovation in financial services. It will unsettle VCs and the Wall Street banks that make boatloads of money selling shares in venture stage companies to public investors (a/k/a "the high-profit-margin customers"). But VCs are cut from the same cloth as Andy Grove. They are alert to threats and they adapt.

Rejuvinators (non-strategic category)

A "Rejuvinator"is a medium to large company that is in financial distress. They can raise capital using a conventional capital structure, but such a deal doesn't have Performance Stock.

Rejuvinators are a non-strategic category for the Fairshare Model because Aspirants must first demonstrate that Performance Stock can help a company attract and manage human capital. It is also a whimsical category because I see the potential to do something good—rejuvenate the relationship of labor and capital in companies that need to reinvent themselves. This category conjures up established companies that failed to adapt because their leadership was not imaginative or bold enough. Think General Motors, Sears and Roebuck, U.S. Steel, Eastman Kodak and many others.

Here's a thought experiment. Think about the myriad challenges that GM faced, starting in the 1970's, when the era of rising fuel prices began—low mileage products, uncompetitive manufacturing costs and quality. Now, imagine its response if it's capital structure had been based on the Fairshare Model. Surely, if employees had Performance Stock, their response to these developments would have been very different because:

1. They would be able to vote on shareholder matters (i.e., the board of directors, which hires and fires officers; executive compensation), and

2. They would benefit financially if the company met performance targets agreed to by its Investor Stockholders.

Had the interests of capital and labor been better balanced and aligned, the quality of communications, the sense of urgency, responsibility and commitment among all levels of the organization would surely have been better. It seems likely that the United Auto Workers would have approached contract matters differently were its members more concerned about GM's vitality (i.e. they would not have used zero-sum game theory). The union might have been less concerned about wages and benefits were and more interested in enhancing worker training and involvement in process improvement. It seems likely that all employees would have focused more on the long-term health of the company, valued knowledge-based authority (including collaboration) over hierarchical-based authority, and would have been more inclined to take product risks. Simply put, had GM used the Fairshare Model, it is difficult for me to imagine that its decades-long decline would have persisted, let alone led to bankruptcy. I think the Fairshare Model would have helped GM be a more dynamic, vibrant organization. One that would have generated benefits for investors, employees and the communities it operated in.

The standard tonic for an underperforming company is to hire a turnaround CEO who will fix or cull money-losing products and cut expenses (jobs), among other things. There are good reasons for these actions, but they often happen so late that desperate, painful actions seem to be the only option. I purport that the Fairshare Model has the potential to help low-performing companies arrest their decline earlier and, thus, minimize the havoc often associated with a turnaround.

Balance and alignment between capital and labor does not avoid the need for painful adjustments but should help organizations spot underlying problems early and address them in an effective manner.

Possible Variants

Once the conversation about the Fairshare Model gets rolling, the categories of companies are sure to be expanded and refined. I offer two more to provoke your imagination. The first is a bank. The second is essentially a public venture fund that raises capital using a Fairshare Model IPO.

The first idea is inspired by Kim Kaselionis, who had been CEO and chairman of a bank before she founded Breakaway Funding, a crowdfunding platform. [61] She see potential for equity crowdfunding to help small banks attract capital, enabling them to make loans to businesses in their community. Recast the idea so that its by industry—organic farming, solar industry, etc.—and you see additional potential. A bank that utilizes the Fairshare Model could have appeal to a large number of investors who are prepared to define performance in non-traditional ways.

Securities law allows a company to raise capital to invest in other companies. If the company raising the money has a target company in mind for an investment, significant disclosures must be made about the candidate. However, if the company raising the capital has no target companies, there is nothing to disclose other than what is ordinarily required for an issuer. Such a company raises capital for what is known as a "blind pool"or "blank check"offering or a Special Purpose Acquisition Company (a/k/a SPAC).

Such an offering holds beguiling prospect to create venture funds that have an investment criteria that would appeal to a broad range of interests. Here are some possibilities:

- Geo-centric: funded companies will be based in a geographic region or state;

- University-centric: funded companies have a tie to the school (e.g., license intellectual property from it, founders are alumni or come out an affiliated incubator). One idea would be to crowdfund a company that funds work in a research lab; in exchange for the funding, the company would share intellectual property rights with the university; and those who are funded.

- Industry-centric: funded companies will be focus on business sectors that may have difficulty attracting capital from traditional venture funds (e.g., agricultural, natural resource conservation, alternative energy, services for the aged, grocery stores that provide low-cost healthy foods in poor neighborhoods).

- Demographic-affinity: funded companies will appeal to investors because of demographic qualities about the entrepreneurs or their target customers. Segments might be defined by gender, age, ethnicity, etc.

Such initiatives will involve intriguing ideas about how to distribute Performance Stock and what the conversion criteria will be. Indeed, it's possible that some efforts will have such a charitable focus that there is no conversion of Performance Stock at all---it can only vote. These social investing ideas could work with a conventional capital structure, but it seems more likely to actually come to being with the Fairshare Model.

Can One Tell What Category a Company Is?

One can't always tell what kind of strategy a company's executives really have. They can be like a mythical shapeshifter. A Feeder may tell you it's a Feeder….but it might may tell you that it's really an Aspirant. A Pop-Up may think that it's a Feeder or Aspirant. A Spin-Out can't remain a Spin-Out—it must evolve into a Feeder or an Aspirant. And, an Aspirant may wind up being a Feeder after all.

Think of these categories as specific martial arts moves (i.e., a particular kick, block or blow) that are learned separately, then combined in a seamless manner. They highlight scenarios that need attention from attorneys and people with insight into organizational behavior and game theory. Ultimately, though, the ability of shareholder classes to cooperate is the key to making the model work.

Regardless of the "category", early adopters of the Fairshare Model will be intrepid entrepreneurs who are prepared to tackle their Ponderables. [62] They will be practical idealists; focused not only on how to make the model work for them, but also intrigued by the opportunity to reinvent capitalism. What they experience will be of intense interest to many because the Fairshare Model upends traditional precepts about capital formation and the relationship between labor and capital.

- Bad experiences attributed to the model will discourage others from adopting it. As these occur, I hope for fair and balanced analysis as to the nature of the cause. As a practical optimist, I'm confident that any problems with the model can be overcome.

- Fair-to-good experiences will encourage experimentation with new approaches.

- Good-to-great experiences will usher in a new era of venture capital, and, it will prod mature companies to better align the interests of their shareholders and employees.

Onward

We've established that companies that adopt the Fairshare Model will be confident that they can perform and engaged in useful speculation about the types of companies that are likely to adopt it. Importantly, it's been underscored that most of these companies will offer poorer liquidity options than venture stage companies that are brought to market by Wall Street investment banks. The saving grace is that issuers that use the Fairshare Model will offer investors a much lower valuation.

Next, I'll describe the history of the Fairshare Model and speculate on how it will and when it will become the New Normal for how start-up companies raise public venture capital.

[43] A start-up CEO who was otherwise seemed to be an exemplar of virtue once urged me to "go to the dark side"when dealing with prospective investors because he felt pressure to bring capital in.

[44] Stock exchanges have minimum requirements, however. They include assets, number of shareholders and market capitalization. So, secondary trading markets have minimum requirements but are no comparable minimum qualifications to have a public offering.

[45] A comparison of listing requirements are here http://www.venturelawcorp.com/listing_requirement_chart.htm

[46] In December 2007, the SEC adopted scaled down reporting company rules for issuers that have a "public float valuation"of less than $75 million http://www.sec.gov/rules/final/2007/33-8876.pdf

[47] "The 20 Startups Marissa Mayer Has Acquired at Yahoo", by Lauren Indvik, Mashable, Jul. 31, 2013

[48] "The 31 Startups Twitter Has Acquired", by Taylor Casti, Mashable, Sep. 18,2013, http://mashable.com/2013/09/18/twitter-acquisitions/

[49] "Twitter Just Bought a Startup That Could Remake the Service", by Ryan Tate, Wired, Apr. 9, 2014, http://www.wired.com/2014/04/twitter-cover-buy/

[51] The rise in the price of Investor Stock is a measure of performance for this Feeder-it generates conversions of Performance Stock to Investor Stock.

[52] The incorporation document is to a corporation what a constitution is to government. The initial agreement will be defined by the company and its initial investors. Amendments require from shareholders entitled to vote.

[53] A presumed performance can be constructed in many ways.

[54] It was 2% one quarter after the IPO, 4% after two quarters, 6% after three quarters and 8% after four quarters.

[56] The entrepreneurial vision is often centered in one person, the CEO. To keep this discussion from getting more complex, I don't attempt to separate his/her interests from other employees.

[57] In a VC deal, earlier investors can be compelled to invest in a future round or face loss of their position.

[58] It is non-obvious, but a failed public company has intrinsic value. A private company can become publically traded via a "reverse merger"with a failed public company. You can learn more about this type of transaction online.

[59] A VC fund's general partners manage the fund and its investments-they provide labor, not (significant) capital. A funds limited partners provide capital, no labor.

[60] "Clayton Christensen Wants to Transform Capitalism"by Jeff Howe, Wired, Feb. 12, 2013 http://www.wired.com/2013/02/mf-clayton-christensen-wants-to-transform-capitalism/all/

[61] For more information on Breakaway Funding visit www.breakawayfunding.com

[62] The Ponderables are at the end of chapter two.

Karl M. Sjogren *

Contact Karl Sjogren is based in Oakland, CA and can be contacted via email or telephone:

Karl@FairshareModel.com

Phone: (510) 682-8093

The Fairshare Model Website

A native of the Midwest, Karl Sjogren spent most of his adult life in the San Francisco Bay area as a consulting CFO for companies in transition—often in a start-up or turnaround phase. Between 1997 and 2001, Karl was CEO and co-founder of Fairshare, Inc, a frontrunner for the concept of equity crowdfunding. Before it went under in the wake of the dotcom and telecom busts, Fairshare had 16,000 opt-in members. Given the rising interest in equity crowdfunding and changes in securities regulation ushered in by the JOBS Act, Karl decided to write a book about the capital structure that Fairshare sought to promote….”The Fairshare Model”. He hopes to have his book out in Spring 2015. Meanwhile, he is posting chapters on his website www.fairsharemodel.com to crowdvet the material.

Material in this work is for general educational purposes only, and should not be construed as legal advice or legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances, and reflects personal views of the authors and not necessarily those of their firm or any of its clients. For legal advice, please consult your personal lawyer or other appropriate professional. Reproduced with permission from Karl M. Sjogren. This work reflects the law at the time of writing.